As the number of electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in hybrids continues to rise, concerns about their impact on the power grid have emerged. This article examines common claims about EV adoption and the electrical grid's capacity, providing a clear perspective on the issue.

The primary question is whether the electric grid can handle the increased demand, especially as experts predict EVs will account for 58% of global vehicle sales by 2040, compared to just 10% today. Taking the UK as an example, there were 32,697,000 cars at the end of 2020. If all these vehicles charged simultaneously at an average home charger rate of 7 kW, the demand would reach 229 GW — more than twice the nation's current grid capacity of 101 GW.

However, these alarming projections are based on unrealistic assumptions. The scenario of all vehicles charging simultaneously is impossible and fails to consider the gradual nature of EV adoption.

Mass adoption won’t happen overnight for several reasons. EV production cannot scale that quickly, and consumers typically retain their current vehicles for several years before switching. Consequently, not everyone will transition to EVs concurrently, even with increased production capacity.

Will All EVs Charge Simultaneously?

Another misconception is that all EV owners will plug in their vehicles at the same time. This is unlikely, given varied owner behavior and limited charger availability, especially during early adoption phases. This allows the grid time to adapt and manage demand.

For context, if every person in the UK used a washing machine simultaneously, the demand would reach roughly 51.4 GW, exceeding the average daily demand of around 30 GW — yet this never occurs.

To assess realistic impacts, consider typical travel distances and EV efficiency. In Britain, the average annual distance driven per car in 2019 was approximately 6,500 miles. Assuming a median consumption of 0.346 kWh per mile, yearly electricity use per EV would be 2,249 kWh. Multiplying by the total number of vehicles yields an annual energy demand of 73.5 TWh — about 22% of the UK's 2019 electricity generation, far less than the previously suggested 200%.

Similar calculations apply elsewhere. In the EU, with an average annual distance of 7,021 miles per vehicle and stable consumption rates, converting all cars to EVs would demand roughly 21% more electricity generation.

In the U.S., where average travel distances are higher at around 14,000 miles annually, energy consumption per vehicle would be approximately 4,844 kWh per year. This would represent about 33% of total grid production — consistent with studies like those from the Engineering Explained YouTube channel, which estimate a 30% increase necessary if all gasoline cars became electric.

Is There Enough Power for Everyone?

Current data suggests the power grid can accommodate increased EV demand. Over the past decade, electricity demand has declined due to more efficient appliances and reduced industrial activity — down 3% in the U.S. and 18% in the UK during the 2010s.

As EVs replace internal combustion engine vehicles, demand for gasoline — and associated electricity consumption in fuel production — will drop. This shift could free up industrial electricity for vehicle charging.

Increasing Electricity Production Is Feasible

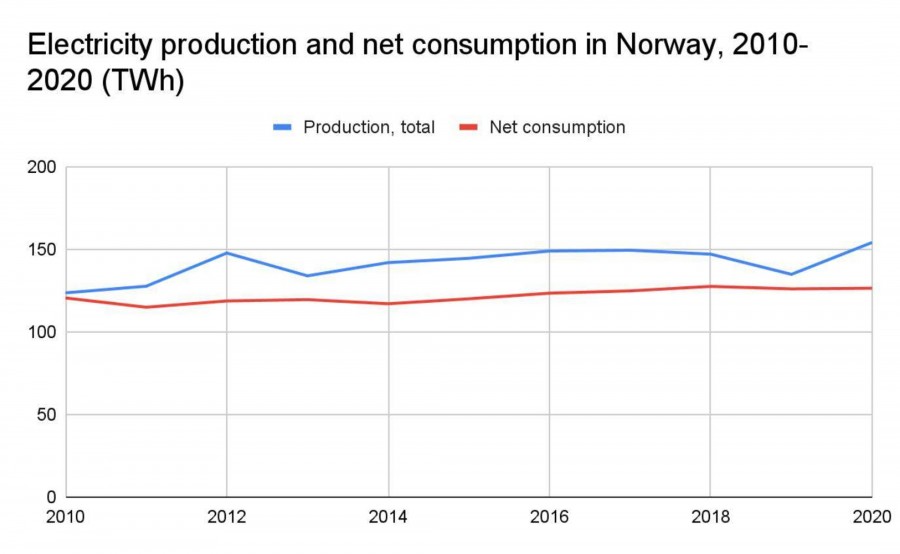

Scaling electricity production to support EV adoption is achievable without radical innovation. Norway exemplifies this, with 12% of vehicles now electric. Since 1990, electricity consumption there has increased by 26%, but production has kept pace.

Source: Statistics Norway

The gradual pace of adoption further mitigates risk. For example, in the UK, registered electric passenger cars rose from 1,544 in 2010 to 314,966 by Q3 2021 — an impressive increase but still a small fraction of total vehicles.

Projections by EY and Eurelectric anticipate 65 million EVs in Europe by 2030 and 130 million by 2035, representing 53% of the current vehicle fleet. Even at these accelerated rates, the grid is expected to remain stable.

In the U.S., studies from U.S. Drive comparing EV adoption to household appliance deployment affirm the grid’s capacity to manage increasing demand under various scenarios.

Addressing Peak Demand Challenges

Though the grid can handle overall demand, peak charging periods may lead to localized stress, causing voltage fluctuations and power losses. Electricity providers will need to invest in upgrading grid capacity, especially on the distribution end.

Incentivizing off-peak charging through lower nighttime rates is already common and could be expanded. Smart grids and emerging vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology offer additional solutions by enabling EVs to both draw from and supply power to the grid during peak and off-peak hours.

However, V2G technology faces challenges such as battery degradation from extra charge cycles and consumer reluctance to use EVs primarily as grid storage. Despite these hurdles, V2G combined with smart grids could play a valuable role in localized, renewable-powered systems.

Looking Ahead

The key takeaway is that the power grid can accommodate EV growth, especially due to gradual adoption and technological advances. Past shifts in electricity use—from basic lighting to heavy appliance reliance—have similarly been managed without collapse.

Renewable energy sources, smart grids, and battery storage provide tools that were unavailable during previous energy transitions. These advancements reduce the risk of grid failure as EV adoption accelerates.

Ultimately, there’s no need for undue concern over the grid’s capacity in response to electric vehicles. Instead, we can focus on enjoying the benefits of cleaner, more efficient transportation without anxiety about energy supply.

Summary

Widespread EV adoption will increase electricity demand, but studies show the power grid can accommodate this growth. Gradual adoption, improved energy efficiency, and emerging technologies like smart grids and vehicle-to-grid solutions mitigate risks. Concerns about grid overload are largely based on unrealistic scenarios.

Photo source: Unsplash